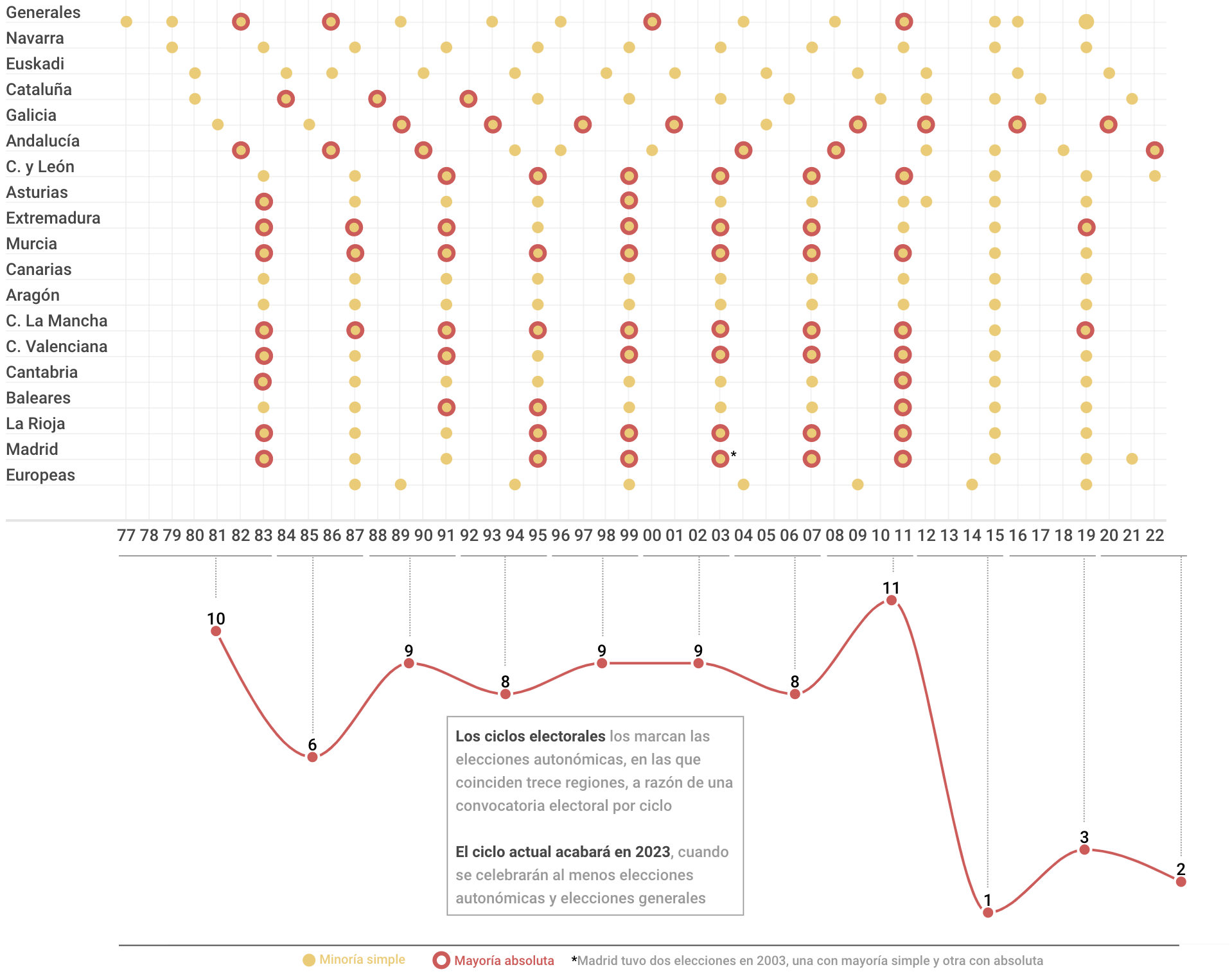

Since the first democratic elections were held in 1977, Spain has experienced more than 200 electoral processes. The number is almost exact (198) if the European, general and those of each of the autonomies are taken into account. And, of them, almost half (76) have had an absolute majority as a result.

But just as in the recent history of Spain there is a before and after in the Transition, democracy has also experienced different periods with marked trends. And with regard to absolute majorities, the economic crisis of 2008 had among its consequences the start of a very particular political cycle that we have been in for a few years and in which majorities became a rarity.

Thus, from an average of almost nine absolute majorities per electoral cycle, there was only one in the 2012-2015 cycle and three in the 2016-2019 cycle. The current period, which will end next year with the holding of general elections and the majority of regional elections, has so far lasted two. In other words: since 2012 we have had six absolute majorities, when only the previous year we had registered nine, including the general ones.

And in these that Andalusia arrives, a region in which various parties come into play, and unexpectedly for most polls it registers an absolute majority. And it comes 14 years after the last one. It’s not that it was an unusual phenomenon in times past, but there were only two big games at stake then. In these elections it was expected that at least two others would have the strength to be necessary in order to form a majority. But it has not been that way.

Is Andalusia the first sign of a new cycle change that is already taking shape? Experts predict a change in trend, but not in that sense. “I don’t think the absolute majorities will return, or not in the short or medium term,” he considers Theodore Leon Gross, journalist and political analyst in the media. “What I do think is going to reappear is bipartisanship, a reinforced bipartisanship,” she predicts. “There is a tendency for the extremes to wane. In Podemos it has already happened; in Vox he will still need some time, and with this and the disappearance of Ciudadanos, this reinforcement of the PP and PSOE will be favored ».

Table of Contents

THE WEIGHT OF WEAR AND ECONOMY

Match part of the analysis Edward Bayon, consultant in political communication and strategy, although he believes that this “transformation of the party system” will still take a few years. “Spanish politics will continue to revolve around two large blocks of left and right, at least for now,” he explains. “But given the electoral behavior of recent years, with the manifest inability of the PP and PSOE to reach certain electorates, the return to only two major parties seems unlikely,” he says, referring to the voting bags that maintain the ideological environment of We can or Vox.

But in his opinion, the more or less imminent return to a scheme of two predominant forces does not necessarily imply a return to the Spain of absolute majorities. “Although they occurred, especially in the different autonomous communities, it is no less true that there have always been parliamentary or government agreements at the regional and municipal levels. Even at the national level, PSOE and PP were forced to reach agreements with nationalist forces », he recalls.

political scientist and sociologist Martha Mark, communication consultant at GAD3, points out that this apparent return to bipartisanship comes “at a difficult economic time” which, in his opinion, will draw “an ideal scenario for the Popular Party to govern, although on many occasions with aid” . According to her vision, “the threat of a major economic crisis and the lack of consensus on relevant issues has set off the alarms” of the voters, who have taken refuge in voting for traditional forces, but that does not imply returning from all behind. “We have not returned to a previous bipartisan scheme,” she considers.

In the same way that León Gross talks about the wear and tear of the extremes, Marcos talks about the wear and tear of the Government. A logical wear and tear after years of complicated management, not only due to the pandemic and the crisis derived from the war, but also due to the unprecedented tensions in a coalition government. “Spain will have to get used to the fact that in politics you can agree, and nothing happens,” he predicts, reinforcing the idea that the rise of the two big parties does not have to mean the disappearance of the rest, much less the return of the majorities baggy

In other words, it would be time to get used to variable geometries. “We could once again see PP and PSOE governments alone. In a minority, but in powerful minorities”, says León Gross in this regard. “Now the polls are giving Feijóo around 135-140 seats.” Far from the absolute majority, but with greater solidity than in the last elections. “From there, you can govern alone,” he estimates.

THE ANDALUSIAN ANOMALY

In any case, he warns about certain questions on the horizon, taking into account what has happened in Andalusia. “There are some factors that I think are interesting to analyze in order to foresee future evolution”, and points to trends such as voting by gender, as has happened with “a clearly partisan female vote”, citing the example of Vox, “where three of every four votes she receives are from men.”

“The case of Andalusia is explained, on the one hand, by the upward trend that the Popular Party is experiencing in this change of cycle, but above all as a consequence of a management that has been endorsed by the Andalusians”, considers Marcos, who He believes that for this reason “extending these majorities to the rest of the territories is not going to be as easy as it seems.”

Along the same lines, León Gross points to another oddity that has taken place in the Andalusian call: the “de-ideologization of the vote with a more pragmatic character” given that, according to data from GAD3, “almost a quarter of a million socialist voters have voted to the People’s Party. It is a support that he defines as “provided” and to which he predicts “a limited duration, of a legislature, since it is not easy to repeat it”, but which has helped shape this unexpected rarity. And more so being a territory in which historically there have been large majorities, although it is not precisely the one that has lived the most.

Results of the elections in Andalusia

In fact, the data shows that there are regions where majorities have traditionally been strong, such as Murcia, the Valencian Community, La Rioja, Castilla y León or the Community of Madrid. However, all of them changed step with the emergence of new parties. Others, such as Castilla-La Mancha, Galicia or Extremadura, have not even done so.

“The Andalusian case does not serve as a reference because it has the singularity of the previous four decades of socialist hegemony”, considers León Gross. And Eduardo Bayón agrees: “What happened in Andalusia responds to a very particular situation marked by the political trajectory of this territory in recent years,” he emphasizes.

«The other three exceptions, Castilla-La Mancha, Galicia or Extremadura, are, in turn, territories that have always had a hegemonic party that, after a temporary loss of the Government, have recovered it». They are, effectively, the only territories that have experienced majorities in this period of change. More rural areas, where Podemos and Ciudadanos, of a much more urban nature, did not achieve capillarity.

But that is no longer a guarantee of anything. Vox, as it demonstrated in the elections in Castilla y León, has managed to break down the wall between the urban and the rural and has become strong in areas until now reserved for the PSOE and the PP. Only two regions have managed to question this trend: the very rural Galicia, where the Feijóo phenomenon has blocked the way first to Ciudadanos and then to Vox, and the Andalusian surprise last month, where Vox has grown but has not managed to skyrocket as expected.

And meanwhile, on the other side of the electoral trends, there are regions that not only do not see the return of absolute majorities as possible, but also seem impossible due to their electoral composition. These are those that have relevant forces beyond traditional bipartisanship, such as Catalonia, the Valencian Community, the Balearic Islands, Cantabria or Asturias.

But, above all, those in which government pacts have been an inevitable maxim: the Canary Islands, Aragon, Navarra and Euskadi are the only four regions in which majorities have never been absolute. And there the negotiation and the agreement have been inexorable maxims, even when the politics of blocs and the need to reach government agreements were not in fashion.